The visual model of the Window of Tolerance and the Polyvagal Theory has been widely used to make sense of what we do in trauma therapy. What they have in common is the underlying assumption that life is interaction with threats and opportunities, and that much of our responses are implicit and modulated through the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS).

However, force-fitting the Polyvagal Theory into the visual model of the Window of Tolerance can be misleading. This article proposes a different visual model. Much of the article can be grasped through a few charts, with relatively few words of explanation.

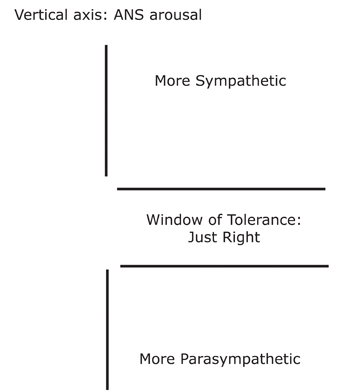

The Window of Tolerance

The Window of Tolerance visual model is a very effective way of stressing some important points.

It illustrates that there is such a thing as too much ANS arousal, or too little ANS arousal, and a “just right” range within which we function optimally. Or, to put it another way: It is good to know whether we are in that range, and important to get back to it when we’re not.

Another benefit of this diagram is to help us define mindfulness in simple, functional terms. Essentially, we are mindful when we are within the window of tolerance. What the diagram shows is that there are different ways that we are not mindful: when there is too much ANS arousal, and when there is too little of it. Hence, there are different ways to come back to mindfulness, depending on where we are.

However, there are some very serious limitations to this model.

There is more to mindful engagement than being in the middle range of ANS arousal

One limitation of the basic model is that it conceives of the “window” only in terms of the sympathetic system and the parasympathetic system balancing each other out. An analogy for this model is what happens when we want to control the temperature of water in a sink: We adjust the cold water faucet and the hot water faucet until we get the water temperature that is neither too cold nor too hot, but just right.

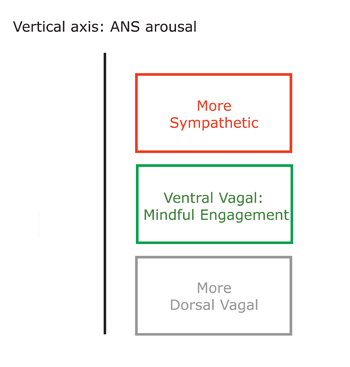

In contrast to the traditional understanding of the ANS, the Polyvagal Theory essentially adds a third “faucet”. The theory points out that the Vagus nerve has two components: the Dorsal part, which mediates the more primitive parasympathetic functions (sleep, shut-down), and the Ventral part, which mediates the more sophisticated functions of social engagement.

The Ventral Vagal system provides the neural connections that allow us to be at our best interacting with other people, with the world, and with ourselves. Moreover, the Ventral Vagal system allows us to regulate the two other systems. This is a far cry from a conception of mindfulness as just being the passive result of two systems balancing each other out.

So it is more accurate to think of mindfulness as a state which is mediated by its own neural network, rather than a window within a continuum of ANS arousal.

These days, while the phrase “window of tolerance” is still used, it is generally meant to refer to the state of Mindful Engagement that occurs when the Ventral Vagal system is on, modulating social engagement. Personally, I prefer not to use that phrase because I find it misleading.

In any case, there is another major problem with this visual model: It does not lend itself to clearly conveying the Polyvagal Theory’s conception of how we handle threats.

The Polyvagal Theory & how we handle threats

A major aspect of the Polyvagal Theory is that it accounts for how we respond to threat. The theory points out that, under threat, the ANS networks are activated in a specific order, ranging from most sophisticated to most primitive. Specifically, we first attempt to respond to threat through the ventral vagal network (social engagement). Then through the sympathetic network (fight or flight). Then, when all else fails, through the most primitive network, the dorsal vagal shut down.

Hence, there is a difference between activation of the dorsal vagal when there is low stimulation (falling asleep) and when there is too much stimulation (actually, an unmanageable threat) for other networks to handle.

Two problems occur if we refer to the above diagram to illustrate the Polyvagal Theory.

One is that we lump together the state of Dorsal Vagal activation that is an essential part of our normal life (e.g. the restorative function of sleep) and the state of Dorsal Vagal activation that is our last resort to deal with a major threat when all else has failed.

Another problem with this visual representation is that it might visually imply that going from Sympathetic activation to Dorsal Vagal immobilization under major threat involves going through the Ventral Vagal state – – which is emphatically not what the Polyvagal Theory observes. The problem stems from the fact that this visual model has just one axis, which represents ANS activation. It does not explicitly take into account the dimension of threat/safety.

See: Conversation with Stephen Porges about the Polyvagal Theory.

The integrated model

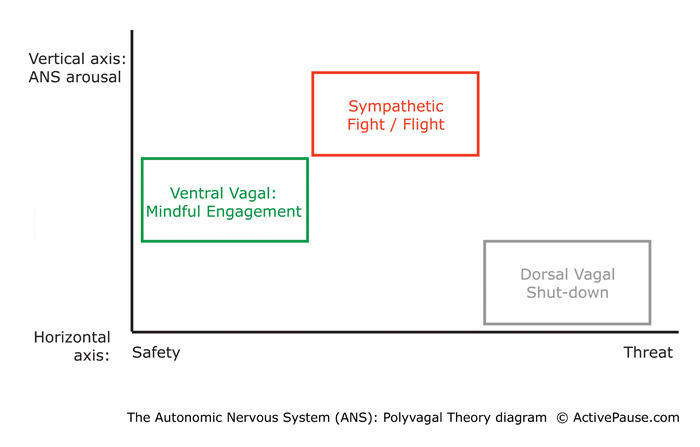

I believe it is important to have a visual model that explicitly takes this dimension of safety/threat into account. In the visual model below, the vertical axis represents ANS arousal (as it does in the basic model of the Window of Tolerance).

There is also a horizontal axis that represents the dimension of safety/threat. This is not an objective measure of threat (the way we can objectively measure weight, or volume) but a visual representation of what we experience, i.e. a given situation can be experienced differently by different people, or even by the same person under different circumstances.

Some of my clients understand the threat dimension better by referring to the notion of control. That is: Some situations are threats we sense we can manage. Some are not a sure thing, but there’s some possibility that we can deal with them, including through fight or flight. And some are overwhelming because we sense that even fight or flight won’t work.

This visual model allows us to clearly differentiate what happens when we are safe (which includes the restorative Dorsal Vagal) from what can happen when we are under threat (which can include Dorsal Vagal Shut-down).

It also reflects the hierarchy of how the systems get activated under threat: Ventral Vagal, then Sympathetic Fight/Flight, then Dorsal Vagal Shut-down. Activation of the Sympathetic Fight/Flight manifests in hyperarousal, whereas activation of the Dorsal Vagal manifests in hypoarousal.

A note on the colors used in the above diagram:

Colors may mean something different to you from what they mean to me. To reduce the possibility of misunderstandings, here are some notes on why I picked the colors I used.

For Ventral Vagal, green felt right, as it implies to me a sense of “you can move” and the generally positive connotation of sustainable energy.

As I am using “green” for “go,” there is the danger of identifying with the “traffic lights” symbols. If so, red would mean “stop” and might represent Dorsal Vagal. I didn’t want that for two reasons: (1) red is a very vibrant color (which is why it is so useful to catch people’s attention, ordering them to stop). The vibrancy and intensity do not feel right to me to represent Dorsal Vagal, and feel more appropriate for the high arousal of the sympathetic, Fight/Flight mode.

For Dorsal Vagal, the color gray has, for me, a washed-out appearance that communicates the low energy, drained quality of this state.

See also: How we experience the polyvagal states.

Looking more closely at Mindful Engagement

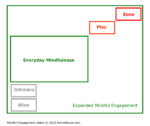

In the visual model above, let’s zoom in on the green rectangle, the one that represents the state of Mindful Engagement.

On the vertical axis, it covers a range of ANS arousal that is within moderate levels. This is not just the effect of the Sympathetic and Dorsal Vagal systems balancing each other out. The Ventral Vagal system itself plays a role in regulating activation.

On the horizontal axis, it covers an area that encompasses safety as well as some degree of threat. It might be more accurate to describe it as a challenge, rather than a threat because it is manageable.

The visual model below represents a “close-up” of the Mindful Engagement rectangle, to illustrate that it encompasses quite a range of self-states, depending on the relative level of activation of the sympathetic network and of the dorsal vagal network.

With relatively more sympathetic activation, we experience self-states of playfulness. At even higher levels, we have the experience of “grace under pressure” or of being in the “zone” of peak performance that athletes aspire to.

With relatively more dorsal vagal activation, we experience self-states of intimacy. The word is not meant as a euphemism for sex, but as a way to describe the sense of openness and closeness that comes from feeling comfortable with our vulnerability because we feel safe. At even higher levels, we have the experience of blissful contemplation (not a state of escaping reality but feeling one with the world while being able to function in it).

This chart is obviously not an exhaustive map of all the various self-states that we can experience when the Ventral Vagal system is on. The point is to take mindfulness away from a narrow context in which it is solely defined as the practice of meditation, by giving examples of different mindful self-states. Doing so gives us a sense of what it is that we have to look forward to in life if we cultivate our potential to experience it.

In therapy, keeping in mind the rich variety of mindful experiences helps us keep our focus on the big picture: We help our clients get more out of life.

Download PDF of Integrated Model

Gratefully acknowledging contributions from Dee Wagner, LPC, BC-DMT.